The UK 4 July General Election was unique on two counts: first, because it witnessed the largest ever presence of candidates to the left of the Labour Party; and second, because five Independent candidates won seats. A total of 330 left-wing candidates challenged the Labour Party in 249 constituencies with the largest contingent coming from George Galloway’s Workers Party of Britain, fighting 152 seats. They were joined by 57 Trotskyist candidates (from a variety of groups, but principally the Socialist Party) and a further 32 candidates belonging to the Communist Party, the Socialist Labour Party and other far left groups. In addition however there was an unprecedented number of left-wing Independent candidates, many of whom were challenging the Labour Party’s position on the Israeli war in Gaza following the 7 October Hamas attack.

Establishing the precise number of left-wing Independents is far from straightforward. The classical Independent candidate is a local activist, convinced their area has been neglected by a succession of mainstream MPs who place party loyalty above the interests of their constituents. So how many of them can be described as left-wing, and by what criteria? Prior to the election, the Muslim Vote website listed 35 left-wing Independents whilst the Collective site counted 55 and the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition reported 62. I used the Democracy Club website to check the personal statements and social media posts of every Independent candidate across all 650 UK constituencies, searching for pro-Palestinian statements and images and for critical views on Labour policies and/or Keir Starmer. In total I found 89 candidates that qualified as left-wing Independents on those criteria including some that were absent from other sites (details available on request).

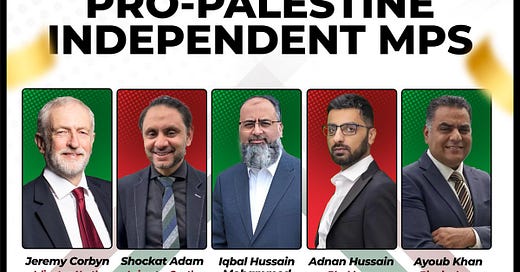

Left-wing Independents secured electoral victories in Birmingham Perry Barr, Blackburn, Dewsbury and Batley and Leicester South, in three cases against Labour incumbents, whilst Jeremy Corbyn comfortably defeated the Labour candidate in Islington North. They might have secured a sixth seat, in Birmingham Ladywood, if two Independents had not run against each other, because their combined vote exceeded the Labour total by 503. In three Conservative seats unsuccessfully targeted by Labour, the size of the left-wing Independent vote was greater than the Tory majority, suggesting they could have gone to Labour in the absence of an Independent challenge (Central Devon, Chingford and Woodford Green and Keighley and Ilkley). In three additional seats, left-wing Independents came a close second to Labour, in Bethnal Green and Stepney, Bradford West and Ilford North, losing out by 1,689, 707 and 528 votes respectively. Further afield, left-wing Independents secured significant vote shares in a range of seats including Slough 25.46%, Ilford South 23.42%, Oldham West, Chadderton and Royton 21.40%, Bradford East 21.25%, Walsall and Bloxwich 20.44%, West Ham and Beckton 19.75%, Holborn and St. Pancras 18.94% and East Ham 17.70%. Moreover, 34 of the 89 left-wing Independents retained their deposits, a significant achievement. That said, their median vote share was just 3.08% indicating that many left-wing Independents performed poorly and some of the electoral victories were underwhelming with vote shares of less than 40% in three cases. Indeed the Blackburn seat was won by the Independent Adnan Hussain with just 27.05% of the vote on a low turnout of 53%, suggesting it is a precarious victory.

In contrast to the electoral successes of the left-wing Independents, George Galloway’s Workers Party of Britain had a very poor campaign, notwithstanding their post-election boast of being the ‘6th largest Britain-wide party’. At the outset of the campaign Galloway declared that he would be ‘extremely disappointed’ if the Party did not secure at least 10 MPs, one of whom would presumably be himself (BBC interview, 1 June). The Workers Party won no MPs at all, not even in their one stronghold of Rochdale, where Galloway failed to consolidate his by-election victory from just three months ago. Despite a significant rise in turnout, his vote actually fell and his vote share dropped ten percentage points. In Birmingham Yardley they came within 700 votes of defeating Jess Philips and in Birmingham Hodge Hill and Solihull North they finished around 1,500 votes behind Labour’s Liam Byrne. Elsewhere however the results were hugely disappointing: over 80% of Workers Party candidates lost their deposits and the Party’s median vote share was just 1.83% with a low median vote of just 721.

Yet if these results were poor, those of the Trotskyists and Communists were even worse. The 57 Trotskyist candidates, 40 of whom stood under the banner of the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition, obtained a median vote of 249 and a median vote share of just 0.65% with only 16 candidates managing to reach even one per cent of the vote. Not surprisingly, all but four of them lost their deposits. Two of those four were candidates in Northern Ireland, standing under the People before Profit banner in Belfast West and Foyle and they maintained their votes and vote shares built up over four General Elections. Two others were nominal, pro-Palestinian independents. Michael Lavalette stood as an ‘Independent’ candidate in Preston, obtaining an impressive vote of 8,719, 21.79% of all votes cast. He is a former local councillor and active member of Counterfire, a small breakaway from the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), and was backed heavily by his organization and extensively promoted on their website. A similar argument applies to Maxine Bowler, a nominal Independent in Sheffield Brightside and Hillsborough but a longstanding member of the SWP who secured 2,537 votes (8.03% of votes cast). We should also mention Fiona Lali, another nominal independent but a prominent member of the Revolutionary Communist Party (formerly Socialist Appeal), because although she lost her deposit she did obtain 1,791 votes in Stratford and Bow (4.12%). None of these three organizations was able to stand candidates under their own names because they are not registered with the Electoral Commission: hence the nominal character of their ‘independence’. Although the Trotskyist results were extremely poor, as they have been for the past 50 years, and suggest little support for the various programmes of revolutionary socialism, the attitude of the Trotskyist movement can best be described as insouciant. The day after the election, Counterfire boldly declared that we should ‘take on Starmer’s government from day one’ (5 July); a Socialist Worker Party feature from 9 July was headlined ‘No honeymoon for new Labour government’; whilst the 10 July Socialist Party paper urged its readers ‘Prepare to fight Labour for the change we need’. Many of them are delighted with the electoral results obtained by pro-Palestinian candidates and seem to believe that their thousands of supporters represent fertile recruiting ground for Trotskyism. However the overwhelmingly religious and socially conservative composition of pro-Palestinian support in areas such as the West Midlands and the North West suggests this is likely to prove a forlorn hope.

Of the remaining far left groups, the Communist Party of Britain stood 14 candidates, its highest total since 1987, but recorded results that were even worse than those of the Trotskyists, with a median vote share of just 0.37% and a median vote of 184. The Socialist Labour Party, founded by former NUM President Arthur Scargill in 1996, stood 12 candidates and achieved an equally derisory result: median vote share 0.69% and median vote 281.

The problems and weaknesses of the overall left challenge to Labour were compounded by the multiplicity of groups seeking votes. Quite apart from the left-wing Independent candidates, and excluding the Green Party for the moment, no less than 17 left and far left parties and organizations contested the 2024 General Election. Amongst these groups there was practically no coordination as to which of them would contest which seats and as a consequence there were widespread clashes. In over one quarter of the seats contested by left-wing candidates, 65 out of 249, there were at least two left-wing organizations campaigning for votes. In nine of these seats, voters were faced a choice of three left-wing candidates and in three seats an astonishing four candidates were appealing to left-wing voters (Blackburn, Plymouth Sutton and Devonport and Stratford and Bow).

In addition to the left-wing Independents, the other significant challenge to Labour came from the Green Party, particularly in urban seats where many Labour candidates were re-elected with reduced votes and lower vote shares. The Greens increased their vote total by approximately one million compared to 2019 and raised their tally of MPs from one to four. Moreover Green candidates finished second to Labour in 39 seats, mostly in big conurbations such as Bristol, London, Manchester and Sheffield.

Overall, the challenge to Labour in the 2024 election did not come from the traditional organized far left, comprising Trotskyist and Communist parties and the Workers Party of Britain, whose votes were on the whole fairly dismal and which failed to elect a single MP. Rather it came from left-wing Independents, angry about Labour’s stance on Gaza and the moderation of its economic policies, and from the Green Party, who together secured the election of nine MPs. In the longer term both of these groupings could provide a far more attractive outlet for disillusioned Labour voters compared to the familiar and unappealing programmes of the revolutionary left.