Why we might be heading for the lowest turnout general election since universal suffrage

The 2024 general election is now just weeks away. Some sections of the public have been calling for it to happen for two years, however there are several reasons it might have the lowest participation rates of any contest in recent history.

The first is the opinion polls. Labour have been ahead of the Conservatives since December 2021, and in the time that Rishi Sunak has been Prime Minister they’ve been consistently polling 20 points ahead of the governing party. The more complex method of MRP polling (multi-level regression with post-stratification) translates this into a Labour majority of 200+ seats in many analyses. Such a shift in the political mood has received widespread media attention, so that even those who pay little attention to politics may now have ‘MRP’ in their lexicon.

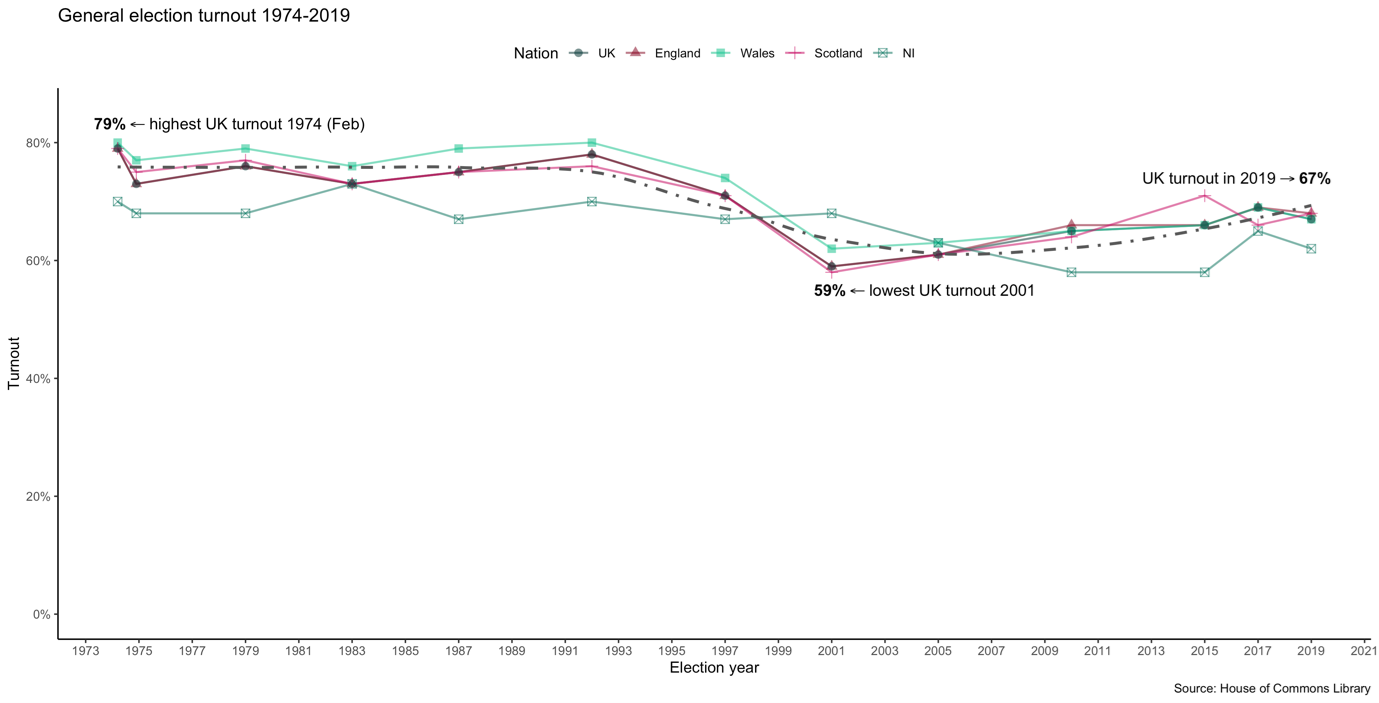

These figures project an image that the result of this election is a foregone conclusion. When comparing turnout rates over the past 50 years, these types of contests see fewer votes cast. In 1983, when it was clear Margaret Thatcher would win a second term, turnout fell three percentage points compared to 1979. Similarly the correctly predicted Labour landslide of 1997 had a seven point lower turnout than 1992. The lowest turnout was 59% when Blair unsurprisingly achieved his second term. Only Scotland has recorded a turnout of more than 70% since then as rates have overall declined in the 21st Century, but the closer fought 2010 election had a four point increase on the previous contest. Turnout across the UK was 67% in 2019.

It has long been theorised, with supporting evidence, that citizens are less motivated to vote when they think it won’t make a difference. With Labour polling so far ahead, this perception is not unwarranted in 2024.

The second reason we might see lower turnout is trust in politicians, or the increasing lack thereof. This has been consistently evoked by the media, party leaders and voters throughout the election campaign. In an Ipsos MORI poll last year, just 9% of people said they trust politicians to tell the truth – the lowest proportion in the 40 years they’ve been asking the question. Trust is positively related to voting, meaning that those who don’t have trust in politics are less likely to cast a ballot. With trust at an all-time low, it's expected to negatively impact turnout.

While local councillors are more trusted at 34% according to Ipsos, they have also suffered a decline. This is accompanied by a trend of lower participation in local elections. The average turnout in 2023 local elections was 32.8%, down nearly ten points over 50 years of local government voting. For some voters in some areas, this discontentment is visible and important.

In contrast, a third factor has gained relatively little attention in this campaign. This is the first general election where the new law requiring photographic ID to vote is in place. The Electoral Commission estimated that 4% of people did not vote in the 2023 local elections because of the new ID law, and that any disenfranchisement is not equally distributed across demographics. The extent of its impact on turnout is yet to be determined as it’s unknown just how many attempted voters that were turned away before they got to the polling station desk. In addition, those voting in local elections tend to be more motivated than those in general elections so they might be more aware of the change in law, or more likely to come back with sufficient ID.

Perhaps the most significant factor that could impact turnout is the increased choice environment. There are more candidates standing than ever before: 77% of constituencies have more candidates standing than did in 2019, and nearly half have eight or more candidates on the ballot. These parties span the full ideological spectrum and include 54 candidates from local parties like the South Devon Alliance. The number of options for voters, and the range of that choice, has significantly increased.

This is compounded by the weaker links between citizens and parties. A high proportion of people are undecided or may change their vote choice before polling day, and they don’t have a strong party identity to rely on to inform their choice. This forces there to be more active choosing, and without a clear preference it is more difficult to arrive at a decision. Some recent political science research and established theory in the decision-making literature suggests that these difficult, forced choices lead people to avoid making a choice at all – in this case, that means not turning out to vote.

Taken together, it gives citizens a number of reasons not to participate. The electorate sees a narrative that the outcome of this election is already a done deal, so they may think their vote won’t make a difference anyway. There are up to eight parties competing for their vote, yet there’s a consistent belief that many of those politicians are not being truthful. It takes more information and a greater cognitive burden to make a decision because there’s more distance between them and the parties on offer. They might even be turned away from a polling station if they forget their ID.

Of course, not all of these factors affect all people, and we know that voting does matter whether your preferred party wins or not. Yet even with a marginal impact, every reason not to vote leads to a greater likelihood of a low turnout – perhaps the lowest any UK general election has seen.

Dr Hannah Bunting is Co-director of The Elections Centre at the University of Exeter and Sky News Elections Analyst. For more insights into British elections, visit https://electionscentre.uk